Purpose and Use of This Guideline

Reviewed and updated: Writing Group; August 11, 2022

Writing group: Joseph P. McGowan, MD, FACP, FIDSA; Steven M. Fine, MD, PhD; Rona Vail, MD; Samuel T. Merrick, MD; Asa Radix, MD, MPH, PhD; Christopher J. Hoffmann, MD, MPH; Charles J. Gonzalez, MD

Committee: Medical Care Criteria Committee

Date of original publication: June 2020

| NEW IN THE 2020 EDITION OF THIS GUIDELINE |

|

This guideline was developed by the New York State Department of Health (NYSDOH) AIDS Institute (AI) for healthcare practitioners in any medical setting (e.g., emergency department, sexual health clinic, urgent care clinic, inpatient unit primary care practice) who manage the care of individuals who request post-exposure prophylaxis (PEP) after a possible exposure to HIV. Despite the availability of prevention measures, exposures occur that pose the risk of transmission. Fortunately, with rapid initiation of PEP, infection can be blocked. Preventing new HIV infections is crucial to the success of New York State’s Ending the Epidemic Initiative.

HIV transmission can be prevented through use of barrier protection during sex (e.g., latex condoms), safer drug injection techniques, and adherence to universal precautions in the healthcare setting. HIV infection can also be prevented with use of antiretroviral (ARV) medications taken as pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP). After an exposure has occurred, HIV infection can be prevented with rapid administration of ARV medications as PEP. The first dose of PEP should be administered within 2 hours of an exposure (ideal) and no later than 72 hours after an exposure.

| KEY POINTS |

|

In addition to clinical recommendations, this guideline details selected good practices and highlights laws and legal considerations that are pertinent in delivering PEP care.

Goals: This guideline aims to achieve the following goals:

- Prevent HIV infection in individuals who experience a high-risk exposure.

- Reinforce that HIV exposure is an emergency that requires rapid response, with immediate administration of the first dose of PEP medications.

- Reduce under- and over-prescribing of PEP by describing the benefits of PEP and providing guidance for identifying high-risk HIV exposures for which PEP is indicated.

- Ensure prescription of PEP regimens that are effective and well tolerated.

- Assist clinicians in recognizing and addressing challenges to successful completion of a PEP regimen.

- Detail the baseline testing, monitoring, and follow-up that should accompany prescription of a 28-day course of PEP.

- Assist clinicians in managing potential concurrent exposures to hepatitis B virus (HBV) and hepatitis C virus (HCV).

How to use this guideline: This guideline is organized to support rapid location of key topics, such as when to initiate PEP, how to evaluate whether continuation of PEP is necessary based on specific risk factors, source testing, how to choose and prescribe a PEP regimen, and recommendations for follow-up care for exposed individuals.

The NYSDOH AI Medical Care Criteria Committee recommendations for prescribing PEP are based on a comprehensive review of available published evidence. In formulating recommendations for NYS, this Committee balanced the strength of published evidence regarding efficacy and timing of initiation of the PEP regimen. See Guideline Development and Recommendation Ratings for a description of the development and ratings processes.

| Icon Key |

All exposures Occupational exposures Non-occupational exposures Sexual assault exposures Exposures in children aged 2 to 12 years |

[bunk]

[e

Risk of Infection Following an Exposure to HIV

Reviewed and updated: Medical Care Criteria Committee; August 11, 2022

Factors that increase the risk of transmission: Many factors that contribute to HIV infection are shared by the 4 PEP scenarios outlined below. HIV transmission risk depends on the viral load of the source with HIV and the type of exposure Sultan, et al. 2014. Factors that increase the risk of HIV transmission include early- and late-stage untreated HIV infection and a high level of HIV RNA in the blood Cardo, et al. 1997, the presence of genital or anorectal ulcers from sexually transmitted infections (STIs), and direct blood-to-blood exchange, such as syringe sharing during injection drug use Kaplan and Heimer 1992; Blank 2005; Johnson and Lewis 2008; Mayer and Venkatesh 2011; Wall, et al. 2017.

Factors that decrease the risk of HIV transmission: Similarly, across the 4 PEP scenarios, there are shared factors that decrease the risk of HIV infection. HIV transmission risk is low and often negligible when the source of the exposure has a low or undetectable viral load Rodger, et al. 2016; Rodger, et al. 2019 and is lower if the source is circumcised (if a cis-gender male and the circumcision is healed) Auvert, et al. 2005; Bailey, et al. 2007; Gray, et al. 2007 or is taking antiretroviral medications as pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) Grant, et al. 2010; Baeten, et al. 2012. In the context of sexual exposure, there is a robust body of evidence that individuals do not sexually transmit HIV if they are taking antiretroviral therapy (ART) and have an undetectable viral load (HIV RNA <200 copies/mL); see NYSDOH AI U=U Guidance for Implementation in Clinical Settings. Data are insufficient to make recommendations regarding HIV transmission via breastfeeding.

Occupational Exposure Risk

The risk of HIV transmission in a healthcare setting has been reported as 0.3% through percutaneous exposure to the blood of a source with HIV Cardo, et al. 1997 and 0.09% after a mucous membrane exposure Kuhar, et al. 2013. In the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Needlestick Surveillance Group study, use of zidovudine (as post-exposure prophylaxis [PEP]) by healthcare workers reduced the risk of HIV acquisition by 81% overall for percutaneous exposures Cardo, et al. 1997. With the use of potent antiretroviral (ARV) medications that have increased bioavailability, it is presumed the use of a 3-drug PEP regimen would significantly reduce this risk further.

In the current era of increasing viral suppression in patients with HIV, early and appropriate PEP initiation, and improved infection control protocols, these rates may be lower. In one cohort of 266 healthcare workers who had percutaneous or mucocutaneous injuries and exposure to HIV-contaminated body fluids, there were zero seroconversions over a 13-year period (seroconversion rate 0%). In addition to their internal findings, the authors compared their results to a calculated overall HIV seroconversion rate of 0.13% after a literature review conducted in October 2016 yielded 17 articles that documented 10 seroconversions among 7,652 healthcare-related exposures Nwaiwu, et al. 2017.

The mean risk may be significantly higher in cases of percutaneous exposure in which more than 1 risk factor is present (e.g., in individuals who incur a deep injury with a hollow-bore needle from a source with HIV and a high viral load). Although the effect of viral load level has not been studied in the patients with occupational exposures, there is evidence that the probability of sexually transmitting HIV is correlated with the source’s HIV viral load Quinn, et al. 2000; Modjarrad, et al. 2008; Attia, et al. 2009.

Prevention of occupational exposure: As part of the employer’s plan to prevent transmission of bloodborne pathogens, the following measures can be taken to avoid injuries:

- Eliminate unnecessary use of needles and other sharps.

- Ensure use of and compliance with devices with safety features.

- Eliminate needle recapping.

- Ensure safe handling and prompt disposal of needles in containers for sharps disposal.

- Provide ongoing education about and promote safe work practices for handling needles and other sharps.

For more information about prevention of needlestick injuries, refer to the NIOSH Alert: Preventing Needlestick Injuries in Health Care Settings NIOSH 1999.

| Resources |

|

Even when effective prevention measures are implemented, exposures to blood and bodily fluid still occur. Employers of personnel covered by the OSHA Bloodborne Pathogen Standard are obligated to provide post-exposure care, including prophylaxis, at no cost to the employee. The employer may subsequently attempt to obtain reimbursement from Workers’ Compensation. See Employer Responsibilities in Management of PEP to Prevent HIV Infection Following an Occupational Exposure for more information.

Non-Occupational Exposure Risk

[_anchor name=box1

| Box 1: Risk per 10,000 Exposures of Acquiring HIV From an Infected Source and Factors That Increase Risk Modified from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention CDC 2015. |

Parenteral Exposure Risk:

Factors that increase risk of transmission through parenteral exposure:

Sexual Exposure Risk:

Factors that increase risk of transmission through sexual exposure:

Other Exposure Types:

Factors that increase risk of transmission through other exposures:

|

Sexual exposures (consensual): Exposures that may prompt a request for non-occupational PEP include condom slippage or breakage; lapse in condom use by serodiscordant or unknown status partners; or other episodic exposure to blood or other potentially infectious body fluids, including semen, vaginal secretions, or body fluids with visible blood contamination. In addition to the viral load of a source with HIV, other factors that influence transmission and acquisition risk include Sultan, et al. 2014:

- Genitorectal trauma

- Type of sexual exposure, i.e., receptive anal, receptive vaginal, insertive anal, insertive vaginal, receptive oral

- Presence of STIs and genital/anal ulcers

- Circumcision status

Condomless receptive anal sex with and without ejaculation carries a risk of 1.43% and 0.65%, respectively. Condomless insertive anal intercourse carries a risk of 0.62% in uncircumcised men and 0.11% in circumcised men Jin, et al. 2010. In one European study, the risk associated with condomless receptive and insertive vaginal intercourse was 0.08% and 0.04%, respectively Mastro and de Vincenzi 1996. Information for patients is available about correct male (insertive) and female (receptive) condom use.

- The CDC’s HIV Risk Reduction Tool can help identify an individual’s risk of acquiring HIV.

Needle sharing and needlestick injuries: Needle sharing among injection drug users is a common reason to request PEP, as the associated risk has been estimated to be as high as 63 per 10,000 exposures based on a study among injection drug users in Thailand Hudgens, et al. 2001; Hudgens, et al. 2002. For this reason, PEP should always be considered in this scenario provided the potential exposure was within 72 hours.

Another route of exposure that prompts requests for PEP is needlestick injury in the community. Factors associated with risk from needlestick injuries include the potential source of the needle, type of needle, presence of blood, and skin penetration.

Individuals who incur needlestick injuries from discarded needles are often concerned about potential HIV exposure. Consideration of potential risk from discarded needles should include the prevalence of HIV in the community or facility where the exposure occurred and the prevalence of injection drug use in the surrounding area. However, the risk of HIV transmission through exposure to dried blood found on syringes is extremely low Zamora, et al. 1998. Discarded needles should not be tested for HIV because of low yield and the risk of injury to personnel involved in the testing.

Vaccination to prevent tetanus and administration of hepatitis B vaccine are indicated for needlestick injures resulting in puncture wounds, based on immunization history and hepatitis B virus status of the source Bader and McKinsey 2013; Stobart-Gallagher 2017. Hepatitis B immunoglobulin may also be necessary (see the guideline sections Management of Potential Exposure to Hepatitis B Virus and Management of Potential Exposure to Hepatitis C Virus).

Bite wounds: An estimated 250,000 human bites occur annually in the United States in a variety of settings American Academy of Pediatrics 1997. Although possible, HIV transmission through bites is thought to be extremely rare. Though many reported instances of bites have occurred, few cases of associated HIV infection have been established. Cases of possible HIV transmission have been documented following bites in adults exposed to blood-tinged saliva Vidmar, et al. 1996; Pretty, et al. 1999. A systematic review found no cases of HIV transmission through spitting and 9 possible cases of HIV transmission through a bite (6 occurred between family members, and 2 involved untrained first responders who placed their fingers in the mouth of an individual who is experiencing a seizure). Only 4 of the 9 cases were confirmed or classified as highly plausible Cresswell, et al. 2018.

A bite wound that results in blood exposure should prompt consideration of PEP. When a human bite occurs, it is possible for both the individual who was bitten and the biter to incur blood exposure (see scenarios listed below). Use of PEP in such a case may be indicated if there is significant exposure to deep, bloody wounds. A bite is not considered a risk exposure to either party when the integrity of the skin is not disrupted.

Scenarios in which bites may result in blood exposure:

- Blood exposure to the biter: When the biter inflicts a wound that breaks the skin and blood from the bitten individual enters the biter’s mouth.

- Blood exposure to the bitten individual: When the biter has blood in his or her mouth (e.g., from bleeding gums or lesions) and inflicts a wound that breaks the skin of the individual bitten.

- Blood exposure to both parties: A break in the skin of the individual who was bitten and the biter has blood in his/her mouth (e.g., from bleeding gums or lesions).

Prevention of non-occupational exposure: Transmission of HIV can be prevented through use of condoms and safer drug injection techniques. HIV infection can be prevented with use of antiretroviral medications as PrEP to protect an individual who engages in behaviors that may result in exposure to HIV. See the NYSDOH AI guideline PrEP to Prevent HIV and Promote Sexual Health > Candidates for PrEP. “Treatment as prevention (TasP)” and “undetectable equals untransmittable (U=U)” are evidence-based strategies for greatly reducing the risk of HIV transmission through sexual exposure; see in NYSDOH AI U=U Guidance for Implementation in Clinical Settings.

Sexual Assault Exposure Risk

Statistics on sexual assault in the United States show high rates of attempted or completed rape among several populations, including cisgender women, men, children, and transgender individuals:

- 21.3% of women reported attempted or completed rape* in their lifetime, with the first assault occurring Smith, et al. 2018:

- Before age 18 years in 43.2% (~11 million)

- Between the ages of 11 and 17 years in 30.5% (~7.8 million)

- At age 10 or younger in 12.7% (~3.2 million)

- 1.4% of men reported attempted or completed rape in their lifetime, with their first experience1 occurring Smith, et al. 2018:

- Before age 18 years in 26% (~2 million)

- Between the ages of 11 and 17 years in 19.2% (~1.5 million)

- 26% of women and 15% of men who were victims of sexual violence, physical violence, or stalking by an intimate partner in their lifetime first experienced these or other forms of violence by that partner before age 18 years CDC(b) 2019.

- 10% of 27,715 respondents to the 2015 U.S. Transgender Survey reported that they had been sexually assaulted in the 12 months prior to survey completion; 47% reported that they had experienced sexual assault during the course of their lives. James, et al. 2016.

*See How NISVS Measured Sexual Violence for definitions. Smith SG, Zhang X, Basile KC, et al. National Intimate Partner and Sexual Violence Survey: 2015 Data Brief – Updated Release. 2018 Nov. https://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/pdf/2015data-brief508.pdf [accessed 2019 Mar 11]

Risk of HIV infection: Increased risk of infection in cases of sexual assault has been associated with trauma at the site of exposure and absence of barrier protection:

- Genitorectal trauma has been documented in 50% to 85% of sexual assault patients Sachs and Chu 2002; Jones, et al. 2009; Sommers, et al. 2012, and anogenital trauma has been observed in 20% to 85% Riggs, et al. 2000; Grossin, et al. 2003; Jones, et al. 2003; Sugar, et al. 2004; Laitinen, et al. 2013; Larsen, et al. 2015.

- High rates of unprotected receptive anal intercourse (88%) and vaginal penetration (>60%) have been reported Draughon Moret, et al. 2016. Perpetrators of intimate partner violence are not likely to use condoms (or use condoms inconsistently), are likely to force sexual intercourse without a condom and to have sexual intercourse with other partners Raj, et al. 2006; Casey, et al. 2016; Stephenson and Finneran 2017.

PEP is the only proven method of reducing HIV acquisition after exposure, and it should be offered in cases of sexual assault. There are published reports of HIV seroconversion following sexual assault Murphy, et al. 1989; Claydon, et al. 1991; Albert, et al. 1994; Myles, et al. 2000.

Exposure Risk in Children

Lead authors for material on PEP in children: Aracelis Fernandez, MD, with Lisa-Gaye Robinson, MD, and Ruby Fayorsey, MD, with the Medical Care Criteria Committee; June 2020

Although there is evidence to support HIV prophylaxis for perinatal exposure, there are no randomized clinical trials of PEP in children beyond the perinatal period. Types of exposures that may be reported in children include sexual assault, needlesticks, or bite from a child who has HIV, but as noted below, this last type of exposure is no longer likely to occur.

Biting: Biting is a common occurrence among young children and in daycare settings. The levels of HIV detected in saliva alone are very low. The few documented cases of possible HIV transmission following bites occurred in adults exposed to blood-tinged saliva Vidmar, et al. 1996; Pretty, et al. 1999; Andreo, et al. 2004. As mentioned previously, a recent systematic review found no cases of HIV transmission through spitting and 9 possible cases of transmission through biting Cresswell, et al. 2018. A bite is not considered a risk exposure to either party when the integrity of the skin is not disrupted. Because there are so few children with HIV now, it is unlikely that a child would be the source of an HIV exposure.

Sexual abuse: HIV transmission has been described in children who have been sexually abused, and this abuse was identified as the only risk factor for infection Gellert, et al. 1993; Lindegren, et al. 1998. Children might be at increased risk of becoming infected with HIV due to the cervical ectopy in adolescent girls and to the thinness of the vaginal epithelium in prepubertal girls Kleppa, et al. 2015. In addition, children who experience abuse multiple times over an extended period by the same perpetrator are at increased risk due to mucosal trauma with bleeding Dominguez 2000; Smith, et al. 2005; CDC 2016.

Discarded needles: Risk of transmission from discarded needles is thought to be low. In 2 cohorts of children (1 with 59 children and the other with 249) exposed to needlesticks from discarded needles, there was no HIV transmission American Academy of Pediatrics 1999. HIV could not be isolated from the washings of 28 discarded needles from public places and 10 needles collected from a needle exchange program American Academy of Pediatrics 1999. In a Canadian study evaluating 274 pediatric community-acquired needlestick injuries, only 30% of those exposed received PEP, but there were no seroconversions in 189 children tested for HIV after 6 months Papenburg, et al. 2008. These studies, as well as the intolerance of HIV to environmental conditions through exposure to air over time, provide reassuring data regarding the low risk of transmission from this type of exposure. (See Table 1: Baseline Testing Based on Age of Exposed Individual and Type of Exposure and Table 6: Recommended Monitoring after PEP Initiation for recommendations regarding laboratory testing, including for hepatitis C virus, based on type of exposure.)

| KEY POINTS |

|

Rationale for PEP and Evidence of PEP Effectiveness

Reviewed and updated: Medical Care Criteria Committee; August 11, 2022

Lead authors for material on PEP in children: Aracelis Fernandez, MD, with Lisa-Gaye Robinson, MD, and Ruby Fayorsey, MD, with the Medical Care Criteria Committee; June 2020

Post-exposure prophylaxis (PEP) has been established to effectively prevent HIV infection in an exposed individual when initiated within 2 hours (ideal) and no later than 72 hours after an exposure. Rapid and effective response to a reported HIV exposure are key to the successful prevention of HIV infection.

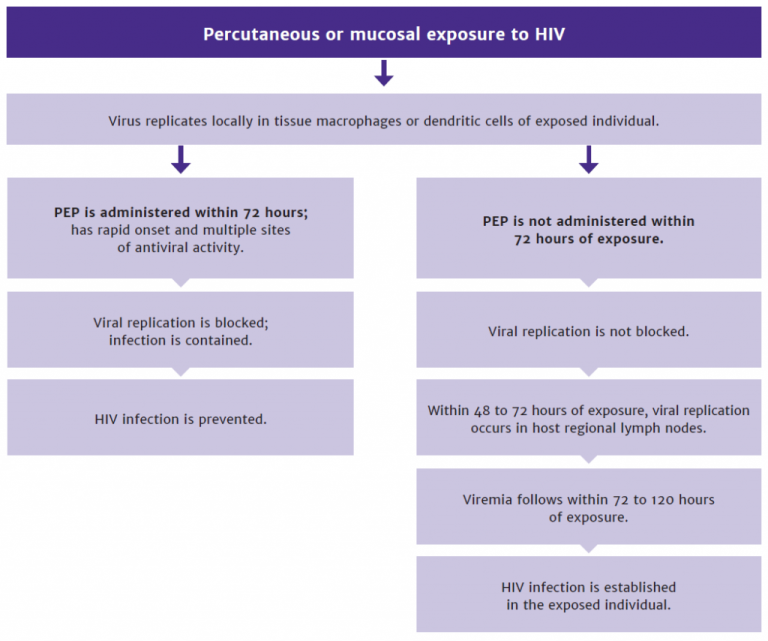

PEP blocks viral replication: After percutaneous or mucosal exposure to HIV, local replication of virus occurs in tissue macrophages or dendritic cells (see Figure 1, below). However, if infection cannot be contained at this stage, it is followed within 48 to 72 hours by replication of HIV in regional lymph nodes. Viremia then follows within 72 to 120 hours (3 to 5 days) of virus inoculation.

This sequence of events carries significant implications. Given the rapid appearance of productively-infected cells following the introduction of virus, PEP regimens with the most rapid onset of activity, multiple sites of antiviral action, and greatest potency are likely most effective.

| KEY POINTS |

|

Evidence of PEP effectiveness: Evidence of PEP effectiveness has been derived primarily from animal model studies and extrapolated from clinical trials of ARV prophylaxis to prevent perinatal transmission of HIV.

Evidence from animal models: Animal studies demonstrate time-dependent efficacy of PEP within 72 hours of exposure, with excellent efficacy reported if initiated within 36 hours Otten, et al. 2000; Tsai, et al. 1998.

- In a recent study, infected mice injected intraperitoneally with fluorescently labeled HIV-1 had no detectable plasma p24 or HIV-1 RNA when treated with raltegravir 1 day post infection. Ten mice that were not treated and became positive for plasma p24 and HIV-1 RNA and developed swollen lymph nodes in the peritoneal cavity Ogata-Aoki, et al. 2018.

- A systematic review and meta-analysis identified 16 studies that specifically assessed the efficacy of PEP (N = 180) compared with controls (N = 103). A pooled analysis of all animal studies reported the risk of seroconversion was 89% lower among primates exposed to PEP than among controls Irvine, et al. 2015.

- In macaques exposed to HIV intravaginally, PEP initiated at 12 and 36 hours post exposure prevented infection; however, breakthrough plasma viremia was observed in some animals when PEP was initiated 72 hours post exposure Otten, et al. 2000.

- SIV infection was prevented in macaques treated 24 hours post exposure with ARV medications as PEP (short-term 9-[2-(R)-(phosphonomethoxy)propyl]adenine); half of the subjects that received PEP at 48 and 72 hours post exposure developed infection Tsai, et al. 1998.

Figure 1: Sequence of Events Following HIV Exposure, With and Without Administration of PEP

NYSDOH-AI-PEP-to-Prevent-HIV-Infection-Figure-1-thumbnail_6-19-20-1024x854

Evidence from human studies: A limited number of case-control studies and clinical trials have established PEP effectiveness in humans.

- Occupational exposure: In a Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) retrospective case-control study of zidovudine (ZDV) use after occupational HIV exposure in healthcare workers, the risk of HIV infection was reduced by 81% in those who received ZDV Cardo, et al. 1997. In a 4-country study, 33 cases of occupationally acquired HIV were compared with 665 control subjects. Case patients were significantly less likely than control subjects to have taken ZDV prophylaxis after exposure, with an odds ratio of 0.19 Cardo, et al. 1997.

- Since 1999, only 1 confirmed case of occupationally acquired HIV has been reported to the CDC Joyce, et al. 2015. In this case, a laboratory technician sustained a needle puncture while working with concentrated HIV cultures, which is a very high-risk scenario.

- PEP following needle sharing and transfusion: No specific studies currently address PEP use and its efficacy among individuals who inject drugs and share needles, and no data are currently available regarding HIV transmission via needle sharing when the source has an undetectable viral load.

- Retrospective analyses of PEP do include small numbers of participants with injection drug use as a risk factor and did not report PEP failures among this group McDougal, et al. 2014; Kahn, et al. 2001.

- One case report demonstrated PEP effectiveness for a 12-year-old girl with sickle cell disease who received 4-drug PEP with tenofovir, emtricitabine, ritonavir-boosted darunavir, and raltegravir after a blood transfusion and exposure to the blood of a donor who had an HIV viral load of 9,740 copies/mL Al-Hajjar, et al. 2014.

Evidence from studies of seroconversion with PEP use after sexual exposure: Observational cohorts have provided some data about seroconversion rates among PEP users and possible risk factors among seroconverters.

- A retrospective study analyzed all non-occupational PEP courses prompted by sexual exposure at a California health center to determine factors associated with seroconversion within 24 weeks of initiating PEP. The incidence rate of HIV infection was 2.3/100 person-years. Of note, 17 seroconversions occurred among 1,744 individuals who followed up within the 24-week period; of these 17 seroconversions, 7 had re-exposure risks, 8 had condom-protected sex only, and 2 reported abstinence from sex following the exposure for which they received PEP. In a multivariate analysis, significant predictors of seroconversion included methamphetamine use, incomplete PEP medication adherence, and time from initial exposure to PEP dose >48 hours but <72 hours Beymer, et al. 2017.

- One systematic review analyzed completion rates among 15 studies (1,830 initiations) of 2-drug PEP regimens and 10 studies (1,755 initiations) of 3-drug PEP regimens. Although the failure rate as determined by HIV seroconversion could not be compared because events overall were rare and protocols for follow-up were not uniform, the data underscore the value and effectiveness of PEP initiation Ford, et al. 2015.

PEP following sexual assault of children and adolescents: One study reported that in an inner-city pediatric emergency department in an area with high HIV prevalence, PEP was offered to 87 survivors of sexual assault who qualified for the intervention. Of those 87 children, only 5.7% were provided with PEP, but 69% were given antibiotic prophylaxis to prevent sexually transmitted infections other than HIV Fajman and Wright 2006. The reasons for such a low number (5 children) of PEP initiations were not provided. Among those who did receive PEP, there was no record of seroconversions, but 2 of those patients were lost to follow-up. The study had many limitations.

First Dose of PEP and Management of the Exposure Site

Reviewed and updated: Medical Care Criteria Committee; August 11, 2022

| RECOMMENDATIONS |

|

[hivlibrarysnippets id=”28468″ |

Note:

|

Exposure to HIV Is an Emergency

An HIV exposure is a medical emergency and rapid initiation of PEP—ideally within 2 hours and no later than 72 hours post exposure—is essential to prevent infection. Therefore, this Committee encourages emergency departments, outpatient clinics, and urgent care centers to train triage staff to assign high priority to patients who report a potential exposure. In deciding whether to continue PEP beyond the first emergency dose, care providers must balance the benefits and risks. PEP can be discontinued later in the evaluation process if indicated.

Because the efficacy of PEP in preventing an established HIV infection diminishes rapidly, initiation as soon as possible after exposure is best Kuhar, et al. 2013; CDC 2016. Animal models have consistently demonstrated improved outcomes at 12 to 36 hours post exposure compared with 72 hours Black 1997; Tsai, et al. 1998; Van Rompay, et al. 1998; Otten, et al. 2000; Smith, et al. 2000; Van Rompay, et al. 2000. Consistent with these findings, the virus can be detected in the regional lymph nodes of SIV-infected rhesus macaques within 2 days of intravaginal exposure Spira, et al. 1996.

| NEW YORK STATE LAW: MINOR CONSENT |

|

| KEY POINTS: TIME TO PROTECTION WITH PREP |

|

PEP for an individual who is taking PrEP: On occasion, an exposed individual who has been taking PrEP may insist on receiving a third ARV medication as PEP despite a clinician’s reassurance that it is not necessary. A clinician may reassure a patient who is taking PrEP with daily adherence that no current evidence can support adding an additional ARV after a potential exposure. However, if the exposed individual has only recently started taking PrEP, has been taking PrEP inconsistently, or has been taking the medications “on-demand,” it may be reasonable to consider a 28-day course of 3-drug PEP after a high-risk exposure. Similarly, if the source has virus with known underlying resistance to the components of a PrEP regimen (emtricitabine or tenofovir), offering 3-drug PEP to the exposed individual should be considered, particularly if the source’s viral load is not suppressed (i.e., <200 copies/mL). Lastly, there may be instances where the clinician may have to balance an exposed individual’s level of anxiety with maintaining the therapeutic alliance between the patient and care provider: offering 3-drug PEP in these scenarios may be appropriate to daily PrEP users in rare circumstances, such as high-risk needle sharing exposures or on a case-by-case basis. A request for PEP from a patient who is consistently using PrEP should not be accommodated following an exposure that is evaluated to be low or zero risk.

Request for PEP later than 72 hours post exposure: Because evidence indicates that PEP is not effective when initiated more than 72 hours post exposure, clinicians should not initiate PEP after this time point Black 1997; Tsai, et al. 1998; Van Rompay, et al. 1998; Otten, et al. 2000; Smith, et al. 2000; Van Rompay, et al. 2000; Beymer, et al. 2017.

| KEY POINT |

|

After 72 hours post exposure, HIV infection may have been established. If PEP is prescribed after 72 hours and then discontinued after 28 days, the risk of viral rebound with that inadvertent interruption in ART is significant, as is the associated risk of developing resistance to ART; therefore, this Committee stresses that PEP should not be initiated later than 72 hours post exposure.

In response to an exposure reported after 72 hours post exposure, follow-up that is appropriate to the type of exposure should be arranged (see Table 1: Baseline Testing Based on Age of Exposed Individual and Type of Exposure):

Occupational exposure: Serial HIV testing, serial hepatitis C virus (HCV) testing, and hepatitis B virus (HBV) prophylaxis if indicated based on prior immunity status (e.g., records of HBV surface antibody titers).

Non-occupational exposure: Serial HIV testing, serial HCV testing, HBV prophylaxis if indicated, and appropriate screening for sexually transmitted infections (STIs). Provide risk-reduction counseling and linkage to PrEP services if indicated.

Sexual assault exposure: Serial HIV testing, serial HCV testing, HBV prophylaxis if indicated, empiric STI treatment, and linkage to appropriate services and support.

Exposure in a child aged 2 to 12 years: Serial HIV testing, HCV antibody testing, HBV prophylaxis if indicated, empiric STI treatment if sexual assault exposure, and linkage to appropriate services and support.

Note: See the guideline section Management of Potential Exposure to Hepatitis B Virus for indications for HBV prophylaxis.

Management of the Exposed Site

Care of the exposure site should prioritize appropriate cleansing and infection preventive measures and minimize further trauma and irritation to the exposed wound site. The site of a wound or needlestick injury should be cleaned with soap and water only. It is best to avoid use of alcohol, hydrogen peroxide, povidone-iodine, or other chemical cleansers. Squeezing the wound may promote hyperemia and inflammation at the wound site, potentially increasing systemic exposure to HIV if present in the contaminating fluid. The use of surgical scrub brushes or other abrasive tools should be avoided, as they can cause further irritation and injury to the wound site. Eyes and other exposed mucous membranes should be flushed immediately with water or isotonic saline.

When to Consult an Expert Regarding the First Dose of PEP

Examples of clinical scenarios that warrant consultation with an experienced HIV care provider include: a source with ARV-resistant HIV, an exposed individual with limited options for PEP medications due to potential drug-drug interactions or comorbidities, or an exposed individual who is pregnant or unconscious.

Expert consultation for New York State clinicians: In such circumstances, clinicians are advised to call the Clinical Education Initiative (CEI Line) to speak with an experienced HIV care provider.

- Call 866-637-2342 and press “1” for HIV PEP. The CEI Line is available 24/7.

The Clinical Consultation Center (CCC) for PEP may be reached by calling 888-448-4911. The CCC is part of the AIDS Education and Training Centers and is located at the University of California, San Francisco/Zuckerberg San Francisco General Hospital. It is funded by the Health Resources and Services Administration and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. See UCSF > PEP for more information, including hours.

| SELECTED GOOD PRACTICE REMINDERS |

|

First Dose of PEP and Management of the Exposure Site

|

Exposure Risk Evaluation

Reviewed and updated: Medical Care Criteria Committee; August 11, 2022

| RECOMMENDATION |

|

[hivlibrarysnippets id=”28483″ |

[_anchor name=box3

| Box 2: Risk of HIV Transmission From a Source With HIV | |

Meaningful risk of transmission:

|

No meaningful risk of transmission:

|

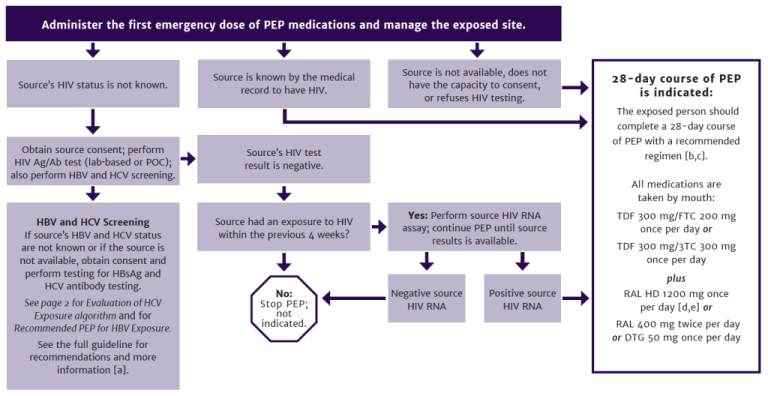

Occupational Exposure Risk Evaluation

PEP is indicated whenever an occupational exposure to blood, visibly bloody fluids, or other potentially infectious material occurs through percutaneous or mucocutaneous routes or through non-intact skin. Figure 2, below, illustrates the steps in determining whether ongoing PEP is indicated after the first emergency dose.

Occupational exposures for which PEP is indicated include the following:

- Break in the skin by a sharp object (including hollow-bore, solid-bore, and cutting needles or broken glassware) that has been in the source’s blood vessel or is contaminated with blood, visibly bloody fluid, or other potentially infectious material.

- Bite from a patient with visible bleeding in the mouth that causes bleeding in the exposed individual.

- PEP is not indicated for an exposure to saliva, including from being spat on, in the absence of visible blood.

- Splash of blood, visibly bloody fluid, or other potentially infectious material to the mouth, nose, or eyes.

- A non-intact skin (e.g., dermatitis, chapped skin, abrasion, or open wound) exposure to blood, visibly bloody fluid, or other potentially infectious material.

Evaluation for other bloodborne pathogens: See the following sections of this guideline: Management of Potential Exposure to Hepatitis B Virus and Management of Potential Exposure to Hepatitis C Virus.

Figure 2: Occupational HIV Exposure: PEP and Exposure Management When Reported Within 72 Hours

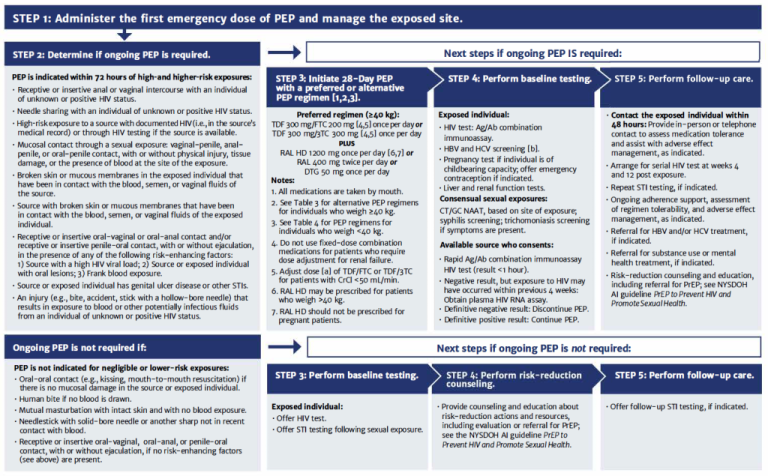

Non-Occupational Exposure Risk Evaluation

In many cases of non-occupational exposure, the source is not available for testing. The HIV status of the source should not be the focus of the initial evaluation; determination of whether the exposure warrants PEP and, when indicated, prompt initiation of PEP, should be the focus. Figure 3, below, illustrates the steps in determining whether ongoing PEP is indicated after the first emergency dose.

| Key Points |

|

Risk of transmission: Box 1: Risk per 10,000 Exposures of Acquiring HIV From an Infected Source and Factors That Increase Risk provides the risk of HIV infection following various types of non-occupational exposure to an individual known to have HIV and factors that may increase risk. HIV transmission occurs most frequently during sexual or drug use exposures; however, many factors can influence risk.

Exposure to a source with acute HIV: Due to the presence of high HIV viral load levels, the probability of transmission when the source is in the acute and early stage of HIV infection (first 6 months) is 8- to almost 12-fold higher than it is once a source’s viral set point has been established, typically about 6 months after infection Pilcher, et al. 2004; Wawer, et al. 2005. The presence of STIs in either the source or the exposed individual also increases risk of HIV transmission Advisory Committee for HIV and STD Prevention 1998; Johnson and Lewis 2008; CDC 2017. Conversely, transmission risk with sexual exposure is significantly decreased when a source is taking effective antiretroviral therapy (ART) and has an undetectable viral load Cohen, et al. 2011 (see NYSDOH AI U=U Guidance for Implementation in Clinical Settings).

Box 3, below, lists non-occupational exposures that should prompt consideration of PEP and those that do not warrant PEP.

| Box 3: Non-Occupational Exposure Risks and Indications for PEP |

Higher-Risk: PEP Is Recommended:

Lower-Risk: Assess Factors That Increase Need for PEP:

PEP Is Not Indicated [b]:

|

|

Abbreviation: PEP, post-exposure prophylaxis. Notes:

|

A frank discussion between the clinician and an exposed individual regarding sexual activities, needle sharing, and other drug-using activities that have the potential for exposure to blood and other body fluids can help determine a patient’s need for PEP (see Boxes 1 and 3). The behaviors that confer the highest risk are needle sharing and receptive unprotected anal intercourse with an individual who has HIV DeGruttola, et al. 1989; CDC 1997; Varghese, et al. 2002.

Clinicians should also assess factors that have been associated with increased risk of HIV infection, including:

- Trauma at the site of exposure, especially if there was contact with blood, semen, or vaginal fluids.

- Presence of genital ulcer disease or other STIs LeGoff, et al. 2007; CDC 2017.

- High plasma viral load in a source with HIV Patterson, et al. 2002; Tovanabutra, et al. 2002.

- Exposure in an uncircumcised male Patterson, et al. 2002; Bailey, et al. 2007; Gray, et al. 2007.

Factors that may significantly decrease transmission of HIV include exposure to a source who is taking effective ART (see NYSDOH AI U=U Guidance for Implementation in Clinical Settings) or use of daily PrEP and use of condoms during sexual exposures Weller and Davis 2002. After consensual sexual exposures that meet NYSDOH U=U Guidance criteria in the source, there is no evidence to support the use of PEP by the exposed individual. Furthermore, there is no evidence that a 3-drug PEP regimen provides any additional benefit to an exposed individual who adheres to a daily PrEP regimen; consistent use of PrEP has been shown to be 99% effective when taken appropriately (see the NYSDOH AI guideline PrEP to Prevent HIV and Promote Sexual Health > PrEP Efficacy). Correct condom use is highly effective in preventing transmission of HIV; however, during the post-exposure evaluation, it often is not possible to reliably ascertain whether condoms were used correctly or whether breakage, slippage, or spillage occurred.

Evaluation for exposure to STIs other than HIV: Risk behaviors leading to HIV infection also confer risk or exposure to other STIs. Patients who present for PEP after a consensual sexual exposure should be evaluated for other STIs.

Baseline testing generally cannot detect STIs that were acquired as a result of the exposure, but it may detect infections present prior to the exposure that prompted the evaluation for PEP. Presentation for PEP provides an opportunity to screen individuals at risk of STIs and treat infections as indicated. High rates of concomitant STIs at the time of presentation for PEP have been found in men who have sex with men Hamlyn, et al. 2006; Jamani, et al. 2013.

Routine empiric treatment for STIs is not recommended for consensual sexual exposures. Education about STI symptoms should be provided, and patients should be instructed to call their healthcare provider if symptoms occur. Follow-up STI screening should be considered at 2 weeks post exposure to definitively exclude STIs Mayer, et al. 2008; Tosini, et al. 2010; Mulka, et al. 2016; Mayer, et al. 2012; Oldenburg, et al. 2015; Mayer, et al. 2017; McAllister, et al. 2017.

Evaluation for other bloodborne pathogens: See the following sections of this guideline: Management of Potential Exposure to Hepatitis B Virus and Management of Potential Exposure to Hepatitis C Virus.

Emergency contraception: For individuals who can but who do not desire to become pregnant, and who consent, emergency contraception should be initiated immediately. There are a range of methods (copper intrauterine device, levonorgestrel, and ulipristal acetate) that can be taken within 5 days of a sexual exposure. Of note, emergency contraception is not an abortifacient and will generally not disrupt an ongoing healthy pregnancy. For more information, see Bedsider: Emergency Contraception.

Figure 3: Non-Occupational HIV Exposure: PEP and Exposure Management When Reported Within 72 Hours

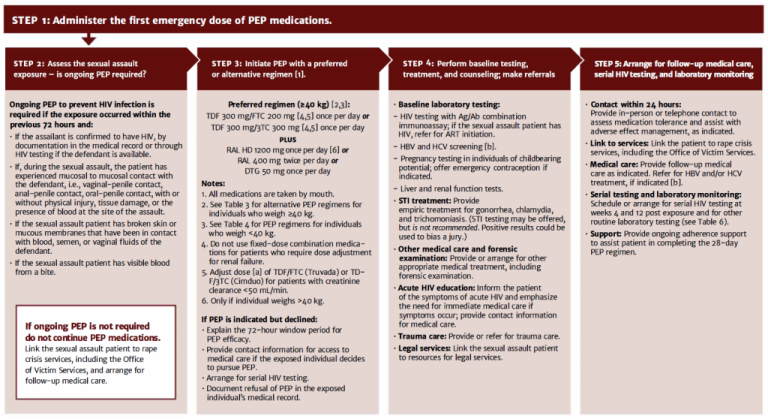

Sexual Assault Exposure Risk Evaluation

The decision to recommend PEP to an individual who may have been exposed to HIV through sexual assault should not be based on the geographic location of the assault but rather on the nature of the exposure during the assault and the HIV status of the defendant, if known. Although the seroprevalence of HIV in different New York State communities may vary, the HIV status of an individual accused of sexual assault remains unknown until that individual has been tested.

| KEY POINTS |

|

Risk of HIV transmission: The risk of HIV transmission in sexual assault is greater due to the presence of genitorectal trauma, which may be present in as many as 50% to 85% of sexual assault patients Sachs and Chu 2002; Jones, et al. 2009; Sommers, et al. 2012. Studies on sexual assault document high rates of unprotected receptive anal intercourse (10% to 15%) and unprotected vaginal penetration (55% to 80%) Draughon Moret, et al. 2016. Studies also demonstrate a wide range (20% to 85%) of incidence of anogenital trauma Riggs, et al. 2000; Grossin, et al. 2003; Jones, et al. 2003; Sugar, et al. 2004; Laitinen, et al. 2013; Larsen, et al. 2015. In one study, 1% of men convicted of sexual assault in Rhode Island had HIV when entering prison Di Giovanni, et al. 1991, higher than the general male population (0.3%).

The absence of visible trauma does not rule out sexual assault; microabrasions and bruising are common, and the appearance of these manifestations following sexual assault may be delayed. Oral trauma may also occur during sexual assault, with potential exposure to blood, semen, or vaginal fluids from the defendant, which may carry a potential risk for HIV exposure. Bites or trauma may be inflicted during an assault and are indications for prophylaxis if there is the possibility of contact with blood, semen, or vaginal fluids from the defendant. A bite from a source with visible bleeding in the mouth that causes bleeding in the exposed individual is an indication for PEP.

HIV testing of the sexual assault patient should be performed in the emergency department setting. HIV testing may be performed on excess blood specimens obtained in the emergency department for other reasons, but only if informed consent has been obtained. In the absence of a baseline HIV test result, it may not be possible to establish that the assault resulted in HIV infection if the patient is later confirmed to have HIV.

If PEP is initiated, then responsibility for monitoring and follow-up should be coordinated by the treating clinician. If the baseline screening HIV test is reactive, then the assault patient should continue the PEP regimen until the result is confirmed with an HIV-1/HIV-2 antibody differentiation immunoassay or HIV RNA test and linkage to care with an experienced HIV care provider has been made. If the patient is not under the care of a primary care clinician, the emergency department clinician who has obtained the HIV test is responsible for ensuring that the patient is informed of the result promptly. If HIV infection has been diagnosed, the PEP regimen may be altered by the HIV care provider or continued in this case as ART.

Every hospital that provides emergency treatment to a sexual assault patient must adhere to and fully document services provided, consistent with the following standards of professional practice and Public Health Law 2805-P:

- Counsel sexual assault patients about options for emergency contraception to prevent pregnancy. Prompt access improves efficacy.

- Provide sexual assault patients with written information about emergency contraception that has been prepared or approved by the NYSDOH.

- Consider a urine pregnancy test to diagnose unplanned pregnancy, similar to STI screening in individuals who may be at risk. Inform the individual that a pregnancy test is being performed.

The following websites offer more information about the use of emergency contraception:

| NEW YORK STATE LAW |

|

STI prophylaxis: Clinicians should offer all sexual assault patients prophylactic medication to prevent gonorrheal and chlamydial infections and trichomoniasis. Rates of STIs have increased in all populations in the United States through a combination of increased incidence of infection and changes in diagnostic, screening, and reporting practices. Surveillance data for the United States indicate that between 2014 and 2018, rates increased for chlamydia (by 19%), gonorrhea (by 64%), primary and secondary syphilis (by 71%) and congenital syphilis(by 185%) CDC 2018; CDC(a) 2019. Trichomoniasis can be diagnosed or excluded in the emergency department if microscopy is available; otherwise, empiric treatment should be administered.

In cases of sexual assault, routine testing for gonorrhea, chlamydia, and syphilis is not recommended because test results would only determine whether the patient had an STI prior to the assault, and this information can be used to bias a jury against a survivor of sexual assault in court NYSDOH 2020.

Evaluation for exposure to HBV: See guideline section Management of Potential Exposure to Hepatitis B Virus.

Evaluation for exposure to HCV: See guideline section Management of Potential Exposure to Hepatitis C Virus.

Figure 4, below, illustrates the steps in determining whether ongoing PEP is indicated after the first emergency dose.

Figure 4: Sexual Assault HIV Exposure: PEP and Exposure Management When Reported Within 72 Hours

Considerations for Sexual Assault in Children

Lead authors for material on PEP in children: Aracelis Fernandez, MD, with Lisa-Gaye Robinson, MD, and Ruby Fayorsey, MD, with the Medical Care Criteria Committee; June 2020

Care providers with experience in managing childhood sexual assault should assist in evaluating children who have been sexually assaulted to best assess the comprehensive needs of the child. Clinicians should assess children who are sexually assaulted for possible exposure to other STIs, including gonorrhea, syphilis, chlamydia, hepatitis B, hepatitis C, and trichomoniasis. Indications for laboratory evaluation and antimicrobial prophylaxis depend on the nature of the assault.

Once the initial, emergency dose of PEP has been administered, care for children exposed to HIV through sexual assault should be managed by a multidisciplinary team that includes the following:

- Clinicians with expertise in providing care for children who have been sexually assaulted

- Child protective services, which are mandated by law to conduct an initial assessment and investigation of reported assault/abuse

- Law enforcement officials to gather and evaluate evidence

- Rape crisis counselors or advocates to provide support to the child and family

- Mental health workers to provide immediate services as needed and who can provide long-term follow-up of the child and family, if appropriate

For more information, see The New York State Child Abuse Medical Provider Program > Education for Child Abuse Medical Providers.

Children who are sexually assaulted should be managed in an emergency department or other setting where appropriate resources are available to address the resulting medical, psychological, and legal issues. Children who present for care following sexual assault may have been victims of multiple exposures over time. PEP is indicated only for a sexual exposure that occurred within the 72 hours prior to the report of sexual assault. However, HIV testing may be indicated if a high-risk exposure occurred after the 72-hour cut-off for PEP efficacy.

For children who may have been exposed to HIV through sexual assault, the decision to continue PEP beyond the first emergency dose should be made based on the exposure evaluation; all sources of sexual exposure in children should be assumed to have HIV unless and until negative status can be confirmed. Clinicians should not delay initiating PEP in an exposed child pending results of the source’s HIV test.

| KEY POINTS: SEXUAL ASSAULT IN CHILDREN |

|

| SELECTED GOOD PRACTICE REMINDERS |

|

[hivlibrarysnippets id=”28503″ |

Source HIV Status and Management

Reviewed and updated: Medical Care Criteria Committee; August 11, 2022

In many cases of non-occupational exposure, the source is not available for testing. The HIV status of the source should not be the focus of the initial evaluation; determination of whether the exposure warrants PEP and, when indicated, prompt initiation of PEP, should be the focus.

| RECOMMENDATIONS |

|

[hivlibrarysnippets id=”28536″ |

If the Source is NOT Available

When the source of any potential exposure to HIV is not known, not available, or cannot be HIV tested for any reason, the care provider should assess the exposed individual’s level of risk, assume the source has HIV until proven otherwise, and respond accordingly.

Determining whether the exposure warrants PEP and promptly initiating PEP when indicated should be the focus at initial presentation, rather than the HIV status of the source.

If the Source IS Available: Test for HIV

When the source is available and consents to HIV testing, use of an HIV-1/2 antigen (Ag)/Ab combination immunoassay is recommended, preferably with a fast turn-around time. Results from point-of-care (POC) assays are available in less than 1 hour, and results from laboratory-based screening tests are often available within 1 to 2 hours. Rapid oral testing is not recommended due to lack of sensitivity to identify recent infection and requirements regarding food, drink, and tobacco use. [_anchor name=box5

| Abbreviations: ART, antiretroviral therapy; PEP, post-exposure prophylaxis. | ||

| Box 4: Source HIV Testing | ||

| Available Source with Confirmed HIV |

Available Source with Unknown HIV Status |

Unknown or Unavailable Source |

|

|

|

| KEY POINTS |

|

When obtaining HIV testing in the source of a potential HIV exposure, consideration must be given to the source’s risk of HIV acquisition in the 4 weeks prior. During this period, often referred to as the “window period” of the HIV-1/2 Ag/Ab combination immunoassay, an initial HIV screening test may be nonreactive. If the source has engaged in condomless sexual intercourse (insertive or receptive anal, penile-vaginal) with or without pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP), or has shared intravenous needles or syringes with or without PrEP, then the source should also be tested for acute HIV infection with an HIV-1 RNA assay (qualitative or quantitative). Please note, only the qualitative HIV-1 RNA assay is U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-approved for aid in diagnosis of HIV.

PEP initiation should not be delayed; the first dose of PEP medications should be administered to the exposed individual before HIV testing and exposure evaluation. Only after the first dose of PEP has been administered should the source’s HIV serostatus, HIV exposure history, and other HIV-related information be evaluated to determine whether to continue PEP.

The most sensitive screening tests available should be used to allow for detection of early or acute HIV infection. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and this Committee recommend screening with an FDA-approved Ag/Ab combination immunoassay, followed by confirmation with an FDA-approved HIV-1/HIV-2 Ab differentiation immunoassay (see the NYSDOH AI guideline HIV Testing and the CDC/American Public Health Laboratories [APHL] Laboratory Testing Algorithm in Serum/Plasma).

Source with confirmed HIV: If the source is known to have HIV, information about their viral load, ART medication history, and history of ART drug resistance should be obtained, when possible, to assist in the selection of a regimen if PEP is indicated Beltrami, et al. 2003. Administration of the exposed individual’s first emergency dose of PEP should not be delayed while awaiting this information.

When a sexual exposure to a source with HIV occurs, the exposed individual may discontinue PEP if the source is taking ART and has an undetectable viral load at the time of exposure. In that scenario, providing information about U=U to the exposed individual and may be reassuring. However, if an exposed individual requests PEP, it should not be denied (see NYSDOH AI U=U Guidance for Implementation in Clinical Settings).

Informed consent: If the source is available and has an unconfirmed HIV status, then consent for voluntary HIV testing should be sought as soon as possible after the exposure. Clinicians should follow individual institutional policies for obtaining consent for HIV testing of the source. In New York State, when the source has the capacity to consent to HIV testing, that individual should be informed that HIV testing will be performed unless the source objects.

If the source objects, the care provider should inform the source that an HIV exposure may require the exposed individual to take medications to prevent infection, and the results of the source’s HIV test could help determine the duration of the exposed individual’s treatment. This information may encourage the source to agree to testing. However, if the source continues to refuse, then HIV testing cannot be performed.

| Box 5: Clinician-to-Clinician Communication |

Occupational exposure: Communication between clinicians is allowed; source information may be shared. Non-occupational exposure: Source information may be shared only if the source signs an Authorization for Release of Health Information and Confidential HIV-Related Information form DOH-2557. Sexual assault exposure: As of November 1, 2007, New York State Criminal Procedure Law § 210.16 requires HIV testing of criminal defendants indicted for certain felony sex offenses when requested by the individual who was assaulted. For guidance on defendant testing, please see New York State Court-Ordered HIV Testing of Defendants. Exposure in a child: Source information may be shared only if the source signs an Authorization for Release of Health Information and Confidential HIV-Related Information form DOH-2557. |

HIV testing in the source of an occupational exposure: If a source does not have the capacity to consent, consent may be obtained from a surrogate, or anonymous testing may be performed if a surrogate is not immediately available (see Box 6, below). Clinicians should follow individual institutional policies for obtaining consent.

| Box 6: HIV Testing When the Source of an Occupational Exposure Is Unable to Consent |

Source: NYSDOH AI Occupational Exposure and HIV Testing: Fact Sheet and Frequently Asked Questions |

| Key Point |

|

HIV testing in the source of a non-occupational exposure when the source is taking PrEP: If the source is taking PrEP, then plasma HIV RNA testing should be performed if the HIV-1/2 Ag/Ab combination immunoassay is negative, as is recommended for other groups at high risk (such as a source who reports possible exposure to HIV within the previous 4 weeks through sex or needle sharing). A negative viral load test will provide reassurance that the source is adherent to PrEP and allow the clinician and the exposed individual to rely on more than just the verbal report of the source.

HIV testing in the source of a sexual assault exposure: In most instances, the HIV status of the assailant will not be known and cannot be available in sufficient time to influence the decision to initiate PEP. If the HIV status of the defendant is established and confirmed, that knowledge should guide the decision to initiate or continue PEP; if the drug resistance data are available for a defendant with HIV, then that information can be used to tailor the PEP regimen. A negative HIV status of a defendant can determine whether the sexual assault patient should complete the 28-day PEP regimen; discontinuing unnecessary PEP has medical and psychological benefits. See NYSDOH Guidance for HIV Testing of Sexual Assault Defendants for more information.

As of November 1, 2007, New York State Criminal Procedure Law § 210.16 requires testing of criminal defendants indicted for certain felony sex offenses for HIV, upon the request of the victim. For guidance on defendant testing, please visit NYS Court-Ordered HIV Testing of Defendants. Information regarding interpretation of HIV tests can be found in the CDC/APHL Laboratory Testing Algorithm in Serum/Plasma.

The increased risk of HIV transmission can be attributed to risk behavior profiles of the defendant, who engage in high-risk behaviors Klot, et al. 2013.

Confirmed defendant HIV status: If the defendant is confirmed to have HIV, then information about the defendant’s viral load, ART medication history, and history of ART drug resistance should be obtained, if possible, to assist in selection of a PEP regimen Beltrami, et al. 2003. Administration of the first emergency dose of PEP should not be delayed while awaiting this information.

HIV status of defendant is unknown or unconfirmed: Even if the individual reporting sexual assault knows the defendant, assumptions about HIV status or risk should have limited influence on the decision to initiate PEP. Familiarity with the defendant may influence the patient’s perception of risk and their decision to accept PEP. Because HIV risk behaviors and status may be hidden from close friends and family, decisions based on familiarity with the defendant should be made cautiously. It is not possible to know whether a defendant has HIV infection solely by risk behaviors. Categorical judgments should not be made on perceived risk. The decision to offer PEP should be based on whether significant exposure has occurred during the assault rather than on the risk behavior of the defendant.

| SELECTED GOOD PRACTICE REMINDERS |

|

[hivlibrarysnippets id=”28538″ |

Baseline Testing of the Exposed Individual

Reviewed and updated: Medical Care Criteria Committee; August 11, 2022

Lead authors for material on PEP in children: Aracelis Fernandez, MD, with Lisa-Gaye Robinson, MD, and Ruby Fayorsey, MD, with the Medical Care Criteria Committee; June 2020

| RECOMMENDATIONS |

|

[hivlibrarysnippets id=”28550″ |

Baseline HIV testing of the exposed individual identifies individuals who were already infected with HIV at the time of presentation (see Table 1, below). Results may inform decision-making regarding initiation of ART as treatment for established infection or initiation of 28 days of PEP to prevent HIV infection (see the NYSDOH AI guideline When to Initiate ART, With Protocol for Rapid Initiation).

An initial reactive screening result must be confirmed with an HIV Ab differentiation immunoassay, and the PEP regimen should be continued until that result is obtained. Furthermore, the PEP regimen should be continued as rapid ART initiation if the reactive result is confirmed with an Ab differentiation immunoassay or HIV-1 RNA test, and the exposed individual should be referred to an experienced HIV care provider.

| Key Points |

|

Exposed Workers

In cases of occupational exposure, exposed workers should be counseled that it is in their best interest to receive a baseline HIV test to document their HIV status at the time of the exposure. In the rare event of seroconversion following an occupational exposure, a negative baseline test is the only way to show that the exposed worker was infected as a result of the exposure.

Baseline HIV testing of the exposed worker is also used to identify individuals who were infected with HIV at the time of the exposure. This allows decisions to be made regarding the continuation of ART (see the NYSDOH AI guideline When to Initiate ART, With Protocol for Rapid Initiation). If the baseline screening HIV test is reactive, then the exposed worker should continue the PEP regimen until the result is confirmed with an HIV-1/HIV-2 Ab differentiation immunoassay or HIV-1 RNA test and linkage to an HIV care provider has been established.

Individuals who decline baseline HIV testing risk the possibility of treatment interruption should they initiate PEP and refuse HIV baseline testing. However, refusal of baseline testing should not be a reason to withhold PEP in the event that an exposed worker had a high-risk exposure that warrants a 28-day course of PEP. Furthermore, the clinician should allow for testing to be performed within 3 days of PEP initiation to allow the exposed worker the opportunity to make an informed decision and to accommodate any anxiety or stress related to a possible HIV exposure. [_anchor name=table1

Baseline Testing of Exposed Individuals

| Abbreviation: HCV, hepatitis C virus; NAAT, nucleic acid amplification test.

Note: In cases of non-sexual exposure in children aged 2 to 12 years, the medical record should be checked for history of tetanus vaccination.

|

|

| Table 1: Baseline Testing Based on Age of Exposed Individual and Type of Exposure | |

| Test | Age of Exposed Individual and Exposure Type |

| HIV-1/2 antigen/antibody combination immunoassay (HIV RNA testing may be required in some cases and within 72 hours in some cases) |

|

| Serum liver enzymes, blood urea nitrogen, creatinine |

|

| Complete blood count |

|

| Pregnancy (individuals of childbearing capacity) |

|

| Hepatitis B serology panel (surface antigen, surface antibody) |

|

| HCV antibody |

|

| Rapid plasma reagin (RPR) |

|

| Gonorrhea/chlamydia NAAT, by site |

|

| Trichomonas NAAT |

|

| SELECTED GOOD PRACTICE REMINDERS |

|

[hivlibrarysnippets id=”28552″ |

Selecting and Initiating a 28-Day Course of PEP

Reviewed and updated: Medical Care Criteria Committee; August 11, 2022

| RECOMMENDATIONS |

Preferred Regimens [a]

Antiretroviral (ARV) Medications to Avoid for PEP

[hivlibrarysnippets id=”28562″ |

Note:

|

Considerations and Caveats

Suspected seroconversion: If acute HIV infection is suspected at any time, immediate consultation with a clinician experienced in managing acute HIV infection is advised (see the NYSDOH AI guideline Diagnosis and Management of Acute HIV). Clinicians can call the Clinical Education Initiative (CEI Line) to speak with an experienced HIV care provider: 866-637-2342 (press “1” for HIV PEP). The CEI Line is available 24/7.

Source confirmed HIV negative: If the source is confirmed to be HIV negative, the exposed individual’s PEP regimen should be discontinued.

Use of a 3-drug PEP regimen: This Committee recommends a 3-drug ARV regimen as the preferred option once the decision has been made to initiate PEP. When the source is known to have HIV, past and current ARV experience, viral load data, and genotypic or phenotypic resistance data (if available) may indicate the use of an alternative PEP regimen. Consult with an experienced HIV care provider.

Drug-drug interactions and adverse effects: Care providers should advise patients not to take divalent cations (aluminum, calcium, magnesium) or iron supplements concurrently with DTG or RAL. Metformin dosing should be limited to 1 g by mouth per day when an individual is taking DTG concurrently.

Care providers should counsel patients about the low risk of gastrointestinal adverse effects with TDF/FTC, such as nausea, abdominal bloating, and vomiting, along with headache. A low risk of neuropsychiatric effects with DTG may also exist. RAL has been rarely associated with rhabdomyolysis FDA 2013.

| RESOURCES: DRUG-DRUG INTERACTIONS INFORMATION |

Impaired renal function: Exposed individuals who have impaired renal function may require dose adjustments of ARV medications used for PEP and may require additional monitoring while completing a 28-day course of PEP DHHS 2022.

Hepatitis B virus infection: Additional monitoring is required for exposed individuals who have HBV infection.

Tenofovir alafenamide (TAF): Recommended and alternative regimens do not include TAF because evidence suggests decreased vaginal, cervical, and rectal tissue concentrations of the active form (tenofovir diphosphate) in healthy volunteers Cottrell, et al. 2017. This Committee does not recommend including TAF in PEP regimens until further research is completed.

Adherence and completion requirements: The recommended 28-day treatment duration is based on limited animal data and expert opinion Tsai, et al. 1998. Nonetheless, adherence to a full 28-day course of PEP and completion of therapy is important to prevent HIV seroconversion post exposure.

Repeated requests for non-occupational PEP: PEP should not be routinely dismissed solely based on repeated risk behavior or repeat presentation for PEP (see guideline section Risk Reduction).

PEP completion following sexual assault: Limited data exist on the use of antiretroviral therapy (ART) to prevent HIV infection in sexual assault populations. One study demonstrated higher completion rates (66% vs. 42%) among individuals taking TDF/FTC in combination with DTG or RAL, as compared with those taking TDF/FTC plus darunavir (DRV) boosted with ritonavir (RTV) Kumar, et al. 2017, suggesting these regimens are better tolerated in this population.

| SELECTED GOOD PRACTICE REMINDERS |

|

[hivlibrarysnippets id=”28564″ |

Preferred PEP Regimens for Patients Who Weigh ≥40 kg

The medications that comprise the recommended PEP regimens (and substitutions) listed in Table 2: Preferred PEP Regimen for Patients Who Weigh ≥40 kg, below, have favorable adverse effect profiles, fewer potential drug-drug interactions, and expected efficacy similar to older PEP regimens that contained ZDV or PIs. Researchers have reported increased rates of adherence and regimen completion when TDF/FTC or TDF/3TC have been used as components of the PEP regimen Mayer, et al. 2008; Tosini, et al. 2010. Observational cohorts and 1 small randomized study reported improved tolerability with TDF/FTC plus RAL Mulka, et al. 2016; Mayer, et al. 2012; McAllister, et al. 2017. Additionally, TDF/FTC has been highly successful in recent studies of pre-exposure prophylaxis Grant, et al. 2010; Baeten, et al. 2012; Thigpen, et al. 2012. One observational cohort demonstrated high completion rates with TDF/FTC plus DTG McAllister, et al. 2017.

Unlike PIs, which block HIV replication after integration with cellular DNA, all currently recommended medications (TDF/FTC plus DTG or RAL) act before viral integration with cellular DNA, providing a theoretical advantage in preventing establishment of HIV infection.

| KEY POINT |

|

Download Table 2: Preferred PEP Regimen for Patients Who Weigh ≥40 kg [a,b] Printable PDF

| Abbreviations: CrCl, creatinine clearance; PEP, post-exposure prophylaxis.

Notes:

|

|

| Table 2: Preferred PEP Regimen for Patients Who Weigh ≥40 kg [a,b] | |

| Preferred Regimen | Notes |

plus

|

|

Alternative PEP Regimens for Patients Who Weigh ≥40 kg

Table 3, below, lists 2 alternative PEP regimens that are acceptable options when a preferred regimen is not available. They are possibly less well tolerated than the preferred regimen of TDF/FTC plus RAL or DTG, but they are significantly better tolerated than regimens containing ZDV or lopinavir/ritonavir (LPV/RTV). Observational studies have demonstrated excellent tolerability and completion rates Fätkenheuer, et al. 2016; Valin, et al. 2016; Mayer, et al. 2017.

A single-tablet regimen for a patient with adequate kidney function (CrCl >70 mL/min) and no expected drug-drug interactions may be a good option for those who prefer a once-daily, single-tablet PEP regimen. It also allows use of medication assistance programs if a patient has limited medication coverage options.

Drug-drug interactions: The potential for drug-drug interactions in patients receiving PIs or cobicistat (COBI) is increased due to the extensive cytochrome P450 interactions. Clinicians should assess for potential interactions before prescribing a PEP regimen. [_anchor name=table3

Download Table 3: Alternative PEP Regimens for Patients Who Weigh ≥40 kg [a,b] Printable PDF

| Abbreviations: CrCl, creatinine clearance; PEP, post-exposure prophylaxis.

Notes:

|

|

| Table 3: Alternative PEP Regimens for Patients Who Weigh ≥40 kg [a,b] | |

| Alternative Regimens | Notes |

|

For individuals with CrCl <70 mL/min: Fixed-dose single tablet EVG/COBI/TDF/FTC is contraindicated. |

|

For individuals with baseline CrCl <50 mL/min: Adjust dosing of 3TC/FTC plus TDF. |

| KEY POINT |

|

Other alternative PEP regimens: Other alternative PEP regimens may be acceptable in certain situations. Some clinicians continue to favor the use of ZDV in PEP regimens based on the results of a retrospective study supporting the efficacy of the agent Cardo, et al. 1997 and from long-term experience in occupational PEP. Clinicians who continue to prescribe ZDV should recognize and inform patients that the drug is associated with significant adverse effects and that better tolerated agents are available.

Use of LPV/RTV has greater potential for drug-drug interactions and adverse effects than RAL, DTG, or DRV/r (the preferred alternative boosted PI), with little added efficacy benefit expected. Studies have demonstrated decreasing PI resistance among HIV strains Paquet, et al. 2011, suggesting there may be a diminishing benefit to choosing LPV/RTV for its activity against resistant HIV strains. DRV/r has excellent activity against many PI-resistant strains and is better tolerated than LPV/RTV.

This Committee recommends a 3-drug regimen because of the greater likelihood of enhanced effectiveness; however, if tolerability is a concern, use of a 2-drug regimen would be preferred to discontinuing the regimen completely. An early case-control study of occupational exposure demonstrated an 81% reduction in seroconversion with the use of ZDV monotherapy alone Cardo, et al. 1997, suggesting that treatment with any active ARV agent is beneficial in reducing risk. Other studies have investigated 2-drug PEP regimens and found excellent tolerability Mayer, et al. 2008; Kumar, et al. 2017.

PEP Regimens for Patients Who Weigh <40 kg

Lead authors for material on PEP in children: Aracelis Fernandez, MD, with Lisa-Gaye Robinson, MD, and Ruby Fayorsey, MD, with the Medical Care Criteria Committee; June 2020

No clinical studies are available to determine the best regimens for HIV PEP in children. The recommendations for drug choices and dosages presented here follow current U.S. Department of Health and Human Services recommendations in Guidelines for the Use of Antiretroviral Agents in Pediatric HIV Infection, which are based on expert opinion. The recommended regimens reflect experience with ARV combinations that effectively suppress viral replication in children with HIV and with combinations that are well tolerated and increase adherence to PEP. The chosen preferred regimens have demonstrated good potency and tolerability.

The alternative PEP regimens for children are also based on expert opinion. They all have demonstrated potent antiviral activity. However, the PI-containing regimens are often more difficult to tolerate, secondary to gastrointestinal adverse effects. To improve adherence, clinicians can and should prescribe preemptive antiemetics for anticipated gastrointestinal adverse effects.

When choosing a PEP regimen, care providers should consider factors that may affect adherence, such as ARV drug intolerance, regimen complexity, expense, and drug availability. [_anchor name=table4

| Table 4: PEP Regimens for Patients 2 to 12 Years Old Who Weigh <40 kg [a] |

See DHHS for dosing, administration, and additional information about each medication. Each medication name below is linked to a page about that medication. Preferred: Tenofovir disoproxil fumarate (TDF; Viread) plus emtricitabine (FTC; Emtriva) plus raltegravir (RAL; Isentress). TDF/FTC is available as the fixed-dose combination (Truvada).

|

|

NYSDOH-AI-PEP-to-Prevent-HIV-Infection-Tables-2-5_9-6-2022_HG |

| KEY POINTS: SEXUAL ASSAULT IN CHILDREN |

|

| SELECTED GOOD PRACTICE REMINDERS |

|

[hivlibrarysnippets id=”28564″ |

ARV Medications to Avoid for PEP

| RECOMMENDATIONS |

|

[hivlibrarysnippets id=”28560″ |

Newer ARV medications have demonstrated significantly fewer adverse effects than older ARVs. The medications listed in Table 5, below, should be avoided.

[_anchor name=table5

| Table 5: Antiretroviral Medications to Avoid for Post-Exposure Prophylaxis | ||||

| ARV Class | Agent | <40 kg | ≥40 kg | Comments |

| First-generation protease inhibitors |

|

Avoid | Avoid | Poorly tolerated |

| First-generation non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors |

|

Avoid | Avoid |

|

| Nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors |

|

Avoid d4T, ddI, ABC, TAF | Avoid all |

|

| CCR5 antagonist | Maraviroc (MVC; Selzentry) | Avoid | Avoid | Only shows activity against R5-tropic virus |

Consultation with an experienced HIV care provider is recommended before using any of the medications listed above for PEP, or before using etravirine or doravirine, for which limited data exist.

| SELECTED GOOD PRACTICE REMINDERS |

|

Selecting and Initiating a 28-Day Course of PEP

|

PEP During Pregnancy or Breastfeeding

| RECOMMENDATIONS |

|

[hivlibrarysnippets id=”28562″ |

Use of ARV prophylaxis in pregnancy generally does not increase the risk of birth defects DHHS 2022. ARV prophylaxis can prevent HIV transmission during acute infection in pregnancy, when viral loads are extremely high, which is associated with a high risk of infection to the infant Patterson, et al. 2007. No severe adverse effects or adverse pregnancy outcomes have been noted among women taking ART for PEP CDC 2016. However, no clinical trial data regarding PEP use in pregnant individuals are currently available CDC 2016, and data are limited on the use of integrase inhibitors during pregnancy DHHS 2022.

When screening for HIV in pregnant patients, care providers should be aware that detection of early/acute HIV infection requires HIV RNA testing in most instances and should repeat antibody testing as late as the third trimester Wertz, et al. 2011 when screening for HIV infection in pregnant patients.

| KEY POINT |

|

Current U.S. Department of Health and Human Services guidelines require dose adjustments for DRV and atazanavir (ATV) DHHS 2022:

- DRV (Prezista): 600 mg twice per day plus RTV (Norvir) 100 mg twice per day

- ATV (Reyataz): 400 mg once per day plus RTV 100 mg once per day in the third trimester

Although birth defects and adverse effects on human fetuses have generally not been associated with the ARV agents that are currently available, exposure of a fetus to ARV agents during pregnancy carries a theoretical risk of embryotoxicity.

ARV medications to avoid as PEP during pregnancy: The ARV medications to be avoided for PEP above also apply to pregnant individuals. Based on animal data, there has been a theoretical concern for teratogenicity of EFV in the first trimester; however, current federal perinatal guidelines do not preclude its use DHHS 2022; Martinez de Tejada, et al. 2019. ZDV is still recommended for prevention of perinatal HIV transmission.

PEP during breastfeeding: Initiation of PEP in exposed individuals who are breastfeeding requires careful discussion. Both HIV and ARV medications may be found in breast milk; therefore, breastfeeding should be avoided for 3 months after the exposure to prevent HIV transmission and potential drug toxicities American Academy of Pediatrics 2013. Clinicians should discuss the risks and benefits with the patient. The infant’s pediatrician should be informed of any potential exposure to HIV or ARV medications.

| SELECTED GOOD PRACTICE REMINDERS |

|

[hivlibrarysnippets id=”28564″ |

Adherence and Completion of the 28-Day PEP Regimen