Resources for Care Providers

June 2022

Provider Information and Education

New York State Department of Health:

- AIDS Institute Provider Directory (HIV, HCV, PEP, PrEP, Emergency PEP Located at a Pharmacy, Buprenorphine, STI Services, Opioid Overdose Prevention Program)

- AIDS Institute Training Centers

- Beyond Status

- CEI: HIV Primary Care and Prevention, Sexual Health, HCV Treatment, and Drug User Health

- CEI: PEP, PrEP, and HCV Clinical Cards (to attach to name badges; available for NYS care providers)

- Communicable Disease Reporting

- Court-Ordered HIV Testing of Defendants

- Emergency Contraception: What You Need to Know

- Ending the AIDS Epidemic in New York State

- Expedited Partner Therapy

- HIV/AIDS Testing, Reporting and Confidentiality of HIV-Related Information

- HIV/AIDS Laws & Regulations

- HIV Testing, Reporting and Confidentiality in New York State 2017-18 Update: Fact Sheet and Frequently Asked Questions

- Informed Consent for HIV Testing and Access to HIV Care for Adolescents

- Occupational Exposure and HIV Testing FAQ

- Partner Services: What Health Care Providers Need to Know

- Payment Options for Adults and Adolescents for Post Exposure Prophylaxis Following Sexual Assault

- Payment Options for Post‐Exposure Prophylaxis Following Non‐Occupational Exposures Including Sexual Assault

- PrEP and PEP Information & Resources

- Provider Reporting & Partner Services

- Rape Crisis Programs by County

- Rapid Testing for HIV

- Requirements to Report Instances of Suspected Child Abuse or Maltreatment

- Rules, Regulations & Laws

- Sexual Violence Prevention Program

- Sexual Assault Forensic Examiner (SAFE) Program

- Sexually Transmitted Infections

- Wadsworth Center (HIV-1/2 adult and pediatric testing)

New York State:

- Child Abuse Medical Provider Program > Education for Child Abuse Medical Providers

- eHealth Collaborative

- Expanded HIV Testing website

- Office for the Prevention of Domestic Violence

- Office of Victim Services

- Safety and Health

- Workers’ Compensation Board: Information for Health Care Providers

New York City:

- Alliance Against Sexual Assault

- Contact Notification Assistance Program (CNAP)

- Expedited Partner Therapy

- Reporting Diseases and Conditions

- Sexual Health Clinics

- Where to Get PrEP and PEP in New York City

AIDS Education & Training Center: National HIV Curriculum

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention:

Clinical Info HIV.gov: Drug Database

Gay & Lesbian Medical Association: Guidelines for Care of Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender Patients

Infectious Diseases Society of America: Diagnosis of Infectious Diseases

National Coalition for Sexual Health:

- A New Approach to Sexual History Taking: Talking About Pleasure, Problems, and Pride During a Sexual History (videos)

- Sexual Health and Your Patients: A Provider’s Guide

University of California San Francisco (UCSF): Clinician Consultation Center: Post-Exposure Prophylaxis

University of Liverpool: HIV Drug Interactions

U.S. Department of Labor Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA):

Antiretroviral Agents Recommended for PEP

Updated May 2021

The medications listed below include antiretroviral agents recommended for PEP (tenofovir disoproxil fumarate, emtricitabine, and either raltegravir or dolutegravir) as well as alternative antiretroviral drugs that may be used in the setting of potential HIV resistance, toxicity risks, or constraints on the availability of particular agents. For information on all antiretroviral medications, see Antiretroviral Therapy.

More information about these antiretroviral agents, including dosage and dose adjustment, potential adverse events and drug interactions, and FDA pregnancy categories, can be found through the links included in the table All FDA-Approved HIV Medications. Before using these drugs, package inserts should also be consulted.

Recommended PEP medications:

- Tenofovir disoproxil fumarate (TDF)

- Emtricitabine (FTC)

- Raltegravir (RAL)

- Dolutegravir (DTG)—See Use of Dolutegravir in Individuals of Childbearing Capacity, May 2021

- Lamivudine (3TC)—equivalent substitute for emtricitabine

Alternative PEP medications:

FDA Pregnancy Categories

A: Adequate and well-controlled studies of pregnant women fail to demonstrate a risk to the fetus during the first trimester of pregnancy (and there is no evidence of risk during later trimesters).

B: Animal reproduction studies fail to demonstrate a risk to the fetus and adequate and well-controlled studies of pregnant women have not been conducted.

C: Safety in human pregnancy has not been determined, animal studies are either positive for fetal risk or have not been conducted, and the drug should not be used unless the potential benefit outweighs the potential risk to the fetus.

D: Positive evidence of human fetal risk based on adverse reaction data from investigational or marketing experiences, but the potential benefits from the use of the drug in pregnant women may be acceptable despite its potential risks.

X: Studies in animals or reports of adverse reactions have indicated that the risk associated with the use of the drug for pregnant women clearly outweighs any possible benefit.

References

DHHS. Statement on Potential Safety Signal in Infants Born to Women Taking Dolutegravir from the HHS Antiretroviral Guideline Panels. 2018 May 18. https://clinicalinfo.hiv.gov/en/news/statement-potential-safety-signal-infants-born-women-taking-dolutegravir [accessed 2022 May 24]

FDA. FDA Drug Safety Communication: FDA to evaluate potential risk of neural tube birth defects with HIV medicine dolutegravir (Juluca, Tivicay, Triumeq). 2018 Sep 6. https://www.fda.gov/drugs/drug-safety-and-availability/fda-drug-safety-communication-fda-evaluate-potential-risk-neural-tube-birth-defects-hiv-medicine [accessed 2018 May 23]

Guidance for HIV Testing of Sexual Assault Defendants

New York State Department of Health (NYSDOH) AIDS Institute (AI); originally published November 2016; updated February 2020

Purpose of This Guidance

As of November 1, 2007, New York Criminal Procedure Law § 210.16 requires testing of criminal defendants, indicted for certain sex offenses, for HIV, upon the request of the sexual assault survivor.

The NYSDOH is responsible for issuing guidance for the court on the following:

- Medical and psychological benefits to the survivor.

- Appropriate HIV test to be ordered for the defendant.

- Circumstances when follow-up testing for the defendant is recommended.

- Indications for discontinuation of post-exposure prophylaxis (PEP).

The NYSDOH AIDS Institute’s (AI’s) Medical Care Criteria Committee and the Mental Health Guidelines Committee carefully reviewed the issues involved and developed this guidance in 2007 through a consensus-based process, and updated it as needed, most recently in February 2020. As requested, the Committee specifically addressed HIV risk; however, care providers should also consider the risk of transmission of hepatitis B, hepatitis C, and other sexually transmitted infections in any sexual assault patient. The guideline Post-Exposure Prophylaxis (PEP) to Prevent HIV Infection, developed by the Medical Care Criteria Committee of the NYSDOH AI, includes recommendations for the post-exposure management of HIV, hepatitis B virus, and hepatitis C virus in sexual assault patients.

Definitions of Significant Risk of HIV Through Sexual Assault Exposure

The defendant testing law refers to “significant exposure” as defined by 10 NYCRR § 63.10. Post-Exposure Prophylaxis (PEP) to Prevent HIV Infection offers a definition of significant exposure during sexual assault that warrants assessment of the survivor. Both definitions are listed below.

- “Significant risk” as defined by 10 NYCRR § 63.10: Three factors are necessary to create a significant risk of contracting or transmitting HIV infection:

- The presence of a significant-risk body substance, and

- A circumstance that constitutes significant risk for transmitting or contracting HIV infection, and

- The presence of an infectious source and a noninfected person.

- Significant risk body substances: Blood, semen, vaginal secretions, breast milk, tissue, and the following body fluids: cerebrospinal, amniotic, peritoneal, synovial, pericardial, and pleural.

- Circumstances that constitute “significant risk of transmitting or contracting HIV infection” for sexual assault survivors:

- Sexual intercourse (e.g., vaginal, anal, oral) that exposes a noninfected individual to blood, semen, or vaginal secretions of an individual with HIV.

- Sharing of needles and other paraphernalia used for preparing and injecting drugs between individuals with and without HIV.

- Penetrating injuries (such as needlesticks with a hollow-bore needle) with exposure to blood or other potentially infected fluids from a source known to have HIV or whose HIV status is unknown.

- Bite from a person known to have HIV or whose HIV status is unknown with visible bleeding in the mouth that causes bleeding in the exposed person.

- Other circumstances not identified during which a significant-risk body substance (other than breast milk) of an individual with HIV contacts mucous membranes (e.g., eyes, nose, mouth), nonintact skin (e.g., open wound, skin with a dermatitis condition, abraded areas), or the vascular system of an individual without HIV.

- Circumstances that do not involve “significant risk”:

- Kissing if no blood is exchanged due to sores or bleeding gums.

- Exposure to urine, feces, sputum, nasal secretions, saliva, sweat, tears, or vomitus that does not contain blood that is visible to the naked eye.

- Human bites where there is no direct blood-to-blood or blood-to-mucous membrane contact.

- Exposure of intact skin to blood or any other bodily substance.

The NYSDOH AI guideline Post-Exposure Prophylaxis (PEP) to Prevent HIV Infection defines a significant exposure during “sexual assault” as follows:

- When the exposed individual has experienced direct contact of the vagina, penis, anus, or mouth with the semen, vaginal fluids, or blood of a defendant, with or without physical injury, tissue damage, or presence of blood at the site of the assault.

- When the exposed individual’s broken skin or mucous membranes have been in contact with the blood, semen, or vaginal fluids of a defendant.

- When an exposed person has visible blood as a result of bites, i.e., a bite has drawn blood.

Maximizing Medical and Psychological Benefit to the Survivor

Exposure to HIV is an emergency. The sexual assault survivor should be evaluated in an emergency department as soon as possible for treatment and evaluation for PEP. The first dose of PEP medications should be administered as soon as possible—ideally within 2 hours of exposure and no later than 72 hours post-exposure. Studies have shown that the sooner PEP is initiated, the more likely it is to be effective.

A 28-day course of a 3-drug PEP regimen, as outlined in the guideline Post-Exposure Prophylaxis (PEP) to Prevent HIV Infection, should be prescribed if a sexual assault patient experienced a significant exposure to HIV. Clinicians are required by law to provide a 7-day starter pack of PEP medications for all sexual assault patients. Sexual assault patients should receive HIV testing at baseline (within 72 hours of the exposure) and at 4 weeks and 12 weeks post-exposure, even if PEP is declined, as detailed in the guideline, Figure 4: Sexual Assault HIV Exposure: Post-Exposure Prophylaxis (PEP) and Exposure Management When Reported Within 72 Hours.

| New York State Law |

|

Court-Ordered HIV Testing of Defendants 7 to 30 Days from the Time of the Exposure

| PEP GUIDELINE RECOMMENDATION |

|

Rationale for the 7- to 30-day time frame: HIV can be detected as early as 7 days with a 4th-generation HIV Ag/Ab combination test. After 30 days from the time of exposure, the survivor will have completed the 28-day PEP regimen; therefore, the testing recommendations change because the use of the 4th-generation HIV Ag/Ab combination test in addition to the HIV RNA assay is not medically beneficial. See Court-Ordered HIV Testing of Defendants: 30 Days to 6 Months from the Time of the Exposure, below, for the psychological benefit that may be gained from defendant testing after 30 days.

Medical benefit for the survivor when testing the defendant between 7 and 30 days: The only clear medical benefit for the survivor of testing the defendant for HIV would be the discontinuation of PEP to avoid potential toxicity and adverse effects; for this benefit to be realized, the defendant’s test results would need to be available within the 28-day period for which the PEP regimen is prescribed.

The medical decision to discontinue PEP on the part of the survivor should be made only in full consultation with the survivor’s clinician. The survivor’s clinician should consult with a clinician experienced in managing PEP before discontinuing the regimen.

Psychological benefits of defendant testing for the sexual assault survivor: Defendant testing for HIV may have the following psychological benefits for the survivor:

- Providing information that may help the survivor understand the degree of risk for acquiring HIV.

- The comfort of knowing that exposure to HIV is unlikely in those instances when the defendant tests negative on both the 4th-generation HIV Ag/Ab combination test and differentiation assay.

- Allowing the survivor to participate more fully in the decision of whether to continue or discontinue the PEP regimen.

Expert consultation for New York State clinicians: Clinicians are advised to call the Clinical Education Initiative (CEI Line) to speak with an experienced HIV care provider.

- Call 1-866-637-2342, and press “2” for HIV.

- The CEI Line is available from 9 AM to 5 PM, Monday through Friday.

Because the results of the defendant’s test may be the only criterion used to decide to terminate the survivor’s PEP regimen, the committee concluded that it was necessary to exclude the possibility of the defendant being in the acute stage of HIV-1 infection. The acute stage is the stage in which the virus and viral RNA are present in the blood but the person has not developed enough specific antibodies to be detected by an antibody test. An HIV antigen/antibody immunoassay may detect HIV-1 p24 antigen as early as 14 days and will also detect HIV-1 and HIV-2 antibodies produced once seroconversion has occurred. An HIV-1 RNA assay is capable of detecting HIV-1 as soon as 7 days after infection and would establish a diagnosis; therefore, it is important to use both an HIV antigen/antibody immunoassay and a plasma HIV-1 RNA assay when the completion of the victim’s PEP regimen is contingent on the defendant test results. If the HIV antigen/antibody immunoassay is positive, the laboratory should complete the recommended HIV testing algorithm, which includes supplemental testing using an HIV-1/HIV-2 differentiation test (see NYSDOH AI guideline HIV Testing). There is a robust body of evidence that individuals do not sexually transmit HIV if they are taking antiretroviral therapy (ART) and have an undetectable viral load (HIV RNA <200 copies/mL); see NYSDOH AI U=U Guidance for Implementation in Clinical Settings.

Negative test results from both the HIV antigen/antibody screening test and the HIV-1 RNA assay would indicate that the defendant is not infected with HIV and would permit discontinuation of the survivor’s PEP regimen. Positive test results for either the HIV antibodies or HIV-1 RNA assay, or both, would indicate that the defendant has HIV and that the survivor’s PEP regimen should be completed. When making decisions regarding the management of the sexual assault survivor, the defendant should be considered to have HIV until proven otherwise. Table 1, below, outlines the different possibilities of test results, how each result would affect the survivor’s PEP regimen, and the necessary follow up.

|

||

| Table 1: Follow-Up Based on Results of Defendant HIV Testing [a] Performed 7 to 30 Days Post-Sexual Assault | ||

| Defendant Test Results | Survivor PEP | Defendant Retesting and Follow-Up |

|

PEP may be discontinued after consultation with physician. |

|

|

PEP should be continued. |

|

|

PEP should be continued. |

|

|

PEP should be continued. |

|

|

PEP should be continued. |

|

Court-Ordered HIV Testing of Defendants 30 Days to 6 Months from Time of Exposure

- Recommended testing: When performing HIV testing of a defendant, clinicians should use the type of HIV test noted in Table 2, below, based on the amount of time that has passed since the assault:

- 30 days to 6 months post-assault: 4th-generation HIV 1/2 antigen (Ag)/antibody (Ab) combination immunoassay is recommended.

- 30 days to 42 days post-assault: Laboratory-based HIV Ag/Ab immunoassay is recommended.

- 42 days to 6 months post-assault: Point-of-care rapid HIV test or a laboratory-based HIV Ag/Ab immunoassay can be used.

- Reactive results on any type of HIV screening assay should be confirmed in a laboratory using the recommended HIV testing algorithm.

- See the NYSDOH AI guideline HIV Testing.

Medical benefit for the survivor when testing the defendant between 30 days and 6 months: There is no medical benefit for the sexual assault survivor when testing the defendant for HIV during the 30-day to 6-month period. If the survivor chose to receive PEP, the 28-day PEP regimen will have been completed at this point. If the survivor tests negative at 12 weeks, then HIV transmission by exposure from the assault can be excluded.

Psychological benefits for the survivor when testing the defendant between 30 days and 6 months: Defendant testing for HIV that may be mandated by the court for up to 6 months after the assault can have the following psychological benefits for the survivor:

- Providing information that may help the survivor understand the degree of risk for acquiring HIV.

- The comfort of knowing that exposure to HIV is unlikely in those instances when the defendant tests HIV negative.

|

|

| Table 2: Follow-Up Based on Results of Defendant HIV Testing [a] Performed 30 Days to 6 Months Post-Sexual Assault | |

| Defendant Test Results | Defendant Retesting and Follow-Up |

| Negative |

|

| Positive |

|

Responsibilities of the County or State Public Health Officer

If testing the defendant would provide medical benefit to the victim or a psychological benefit to the victim, then the testing is to be conducted by a state, county, or local public health officer designated by the order.

- Responsibilities to the defendant:

- Provide pre-test information.

- Obtain appropriate HIV test(s), depending on the timing of testing in relation to when the exposure occurred.

- Provide post-test counseling.

- Responsibilities to the sexual assault survivor:

- Notify the survivor of the defendant’s test results.

- Instruct the survivor to inform his/her healthcare provider of the results and discuss how to proceed with PEP.

- Responsibility to the court: Notify the court in writing that the test(s) was performed and the results were shared with the sexual assault survivor.

- Disclosure: Disclosure of confidential HIV-related information shall be made to the defendant upon his or her request.

- Disclosure to a person other than the defendant will be limited to the person making the application (i.e., the sexual assault survivor). The survivor may then disclose the defendant’s HIV test results to the survivor’s medical care provider, legal representative, and close family members or legal guardian. The survivor may also share the HIV-related information with his or her sex or needle-sharing partners if it is believed that these individuals were exposed to HIV.

- Survivors cannot disclose the defendant’s name during these discussions.

- Disclosure shall not be permitted to any other person or to the court.

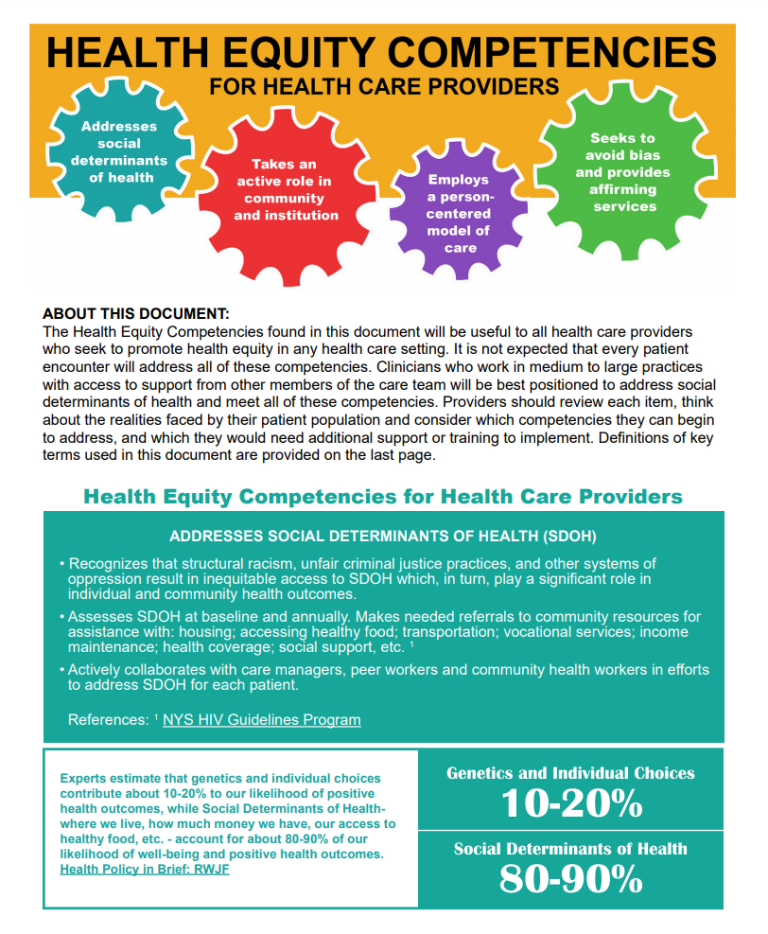

Health Equity Competencies for Health Care Providers

GOALS Framework for Sexual History Taking in Primary Care

Download Printable PDF of GOALS Framework

Developed by Sarit A. Golub, PhD, MPH, Hunter College and Graduate Center, City University of New York, in collaboration with the NYC Department of Health and Mental Hygiene, Bureau of HIV, July 2019

Background: Sexual history taking can be an onerous and awkward task that does not always provide accurate or useful information for patient care. Standard risk assessment questions (e.g., How many partners have you had sex within the last 6 months?; How many times did you have receptive anal sex with a man when he did not use a condom?) may be alienating to patients, discourage honest disclosure, and communicate that the number of partners or acts is the only component of sexual risk and health.

In contrast, the GOALS framework is designed to streamline sexual history conversations and elicit information most useful for identifying an appropriate clinical course of action.

The GOALS framework was developed in response to 4 key findings from the sexual health research literature:

- Universal HIV/STI screening and biomedical prevention education is more beneficial and cost-effective than risk-based screening [Wimberly, et al. 2006; Hoots, et al. 2016; Owusu-Edusei, et al. 2016; Hull, et al. 2017; Lancki, et al. 2018].

- Emphasizing benefits—rather than risks—is more successful in motivating patients toward prevention and care behavior [Weinstein and Klein 1995; Schuz, et al. 2013; Sheeran, et al. 2014].

- Positive interactions with healthcare providers promote engagement in prevention and care [Bakken, et al. 2000; Alexander, et al. 2012; Flickinger, et al. 2013].

- Patients want their healthcare providers to talk with them about sexual health [Marwick 1999; Ryan, et al. 2018].

Rather than seeing sexual history taking as a means to an end, the GOALS framework considers the sexual history taking process as an intervention that will:

- Increase rates of routine HIV/STI screening;

- Increase rates of universal biomedical prevention and contraceptive education;

- Increase patients’ motivation for and commitment to sexual health behavior; and

- Enhance the patient-care provider relationship, making it a lever for sexual health specifically and overall health and wellness in general.

The GOALS framework includes 5 steps:

- Give a preamble that emphasizes sexual health. The healthcare provider briefly introduces the sexual history in a way that de-emphasizes a focus on risk, normalizes sexuality as part of routine healthcare, and opens the door for the patient’s questions.

- Offer opt-out HIV/STI testing and information. The healthcare provider tells the patient that they test everyone for HIV and STIs, normalizing both testing and HIV and STI concerns.

- Ask an open-ended question. The healthcare provider starts the sexual history taking with an open-ended question that allows them to identify the aspects of sexual health that are most important to the patient, while allowing them to hear (and then mirror) the language that the patient uses to describe their body, partner(s), and sexual behaviors.

- Listen for relevant information and fill in the blanks. The healthcare provider asks more pointed questions to elicit information that might be needed for clinical decision-making (e.g., 3-site versus genital-only testing), but these questions are restricted to specific, necessary information. For instance, if a patient has already disclosed that he is a gay man with more than 1 partner, there is no need to ask about the total number of partners or their HIV status in order to recommend STI/HIV testing and PrEP education.

- Suggest a course of action. Consistent with opt-out testing, the healthcare provider offers all patients HIV testing, 3-site STI testing, PrEP education, and contraceptive counseling, unless any of this testing is specifically contraindicated by the sexual history. Rather than focusing on any risk behaviors the patient may be engaging in, this step focuses specifically on the benefits of engaging in prevention behaviors, such as exerting greater control over one’s sex life and sexual health and decreasing anxiety about potential transmission.

Resources for implementation:

- Script, rationale, and goals: Box 1, below, provides a suggested script for each step in the GOALS framework, along with the specific rationale for that step and the goal it is designed to accomplish.

- The 5Ps model for sexual history-taking (CDC): Note that the GOALS framework is not designed to completely replace the 5Ps model (partners, practices, protection from STI, past history of STI, prevention of pregnancy); instead, it provides a framework for identifying information related to the 5Ps that improves patient-care provider communication, reduces the likelihood of bias or missed opportunities, and enhances patients’ motivation for prevention and sexual health behavior.

Download Box 1: GOALS Framework for the Sexual History Printable PDF

| Box 1: GOALS Framework for the Sexual History |

||

| Component | Suggested Script | Rationale and Goal Accomplished |

| Give a preamble that emphasizes sexual health. | I’d like to talk with you for a couple of minutes about your sexuality and sexual health. I talk to all of my patients about sexual health, because it’s such an important part of overall health. Some of my patients have questions or concerns about their sexual health, so I want to make sure I understand what your questions or concerns might be and provide whatever information or other help you might need. |

|

| Offer opt-out HIV/STI testing and information. | First, I like to test all my patients for HIV and other sexually transmitted infections. Do you have any concerns about that? |

|

| Ask an open-ended question. | Pick one (or use an open-ended question that you prefer):

|

|

| Listen for relevant information and probe to fill in the blanks. |

|

|

| Suggest a course of action. |

|

|

References

Alexander JA, Hearld LR, Mittler JN, et al. Patient-physician role relationships and patient activation among individuals with chronic illness. Health Serv Res 2012;47(3 Pt 1):1201-1223. [PMID: 22098418]

Bakken S, Holzemer WL, Brown MA, et al. Relationships between perception of engagement with health care provider and demographic characteristics, health status, and adherence to therapeutic regimen in persons with HIV/AIDS. AIDS Patient Care STDS 2000;14(4):189-197. [PMID: 10806637]

Flickinger TE, Saha S, Moore RD, et al. Higher quality communication and relationships are associated with improved patient engagement in HIV care. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2013;63(3):362-366. [PMID: 23591637]

Hoots BE, Finlayson T, Nerlander L, et al. Willingness to take, use of, and indications for pre-exposure prophylaxis among men who have sex with men-20 US cities, 2014. Clin Infect Dis 2016;63(5):672-677. [PMID: 27282710]

Hull S, Kelley S, Clarke JL. Sexually transmitted infections: Compelling case for an improved screening strategy. Popul Health Manag 2017;20(S1):S1-s11. [PMID: 28920768]

Lancki N, Almirol E, Alon L, et al. Preexposure prophylaxis guidelines have low sensitivity for identifying seroconverters in a sample of young Black MSM in Chicago. Aids 2018;32(3):383-392. [PMID: 29194116]

Marwick C. Survey says patients expect little physician help on sex. Jama 1999;281(23):2173-2174. [PMID: 10376552]

Owusu-Edusei K, Jr., Hoover KW, Gift TL. Cost-effectiveness of opt-out chlamydia testing for high-risk young women in the U.S. Am J Prev Med 2016;51(2):216-224. [PMID: 26952078]

Ryan KL, Arbuckle-Bernstein V, Smith G, et al. Let’s talk about sex: A survey of patients’ preferences when addressing sexual health concerns in a family medicine residency program office. PRiMER 2018;2:23. [PMID: 32818195]

Schüz N, Schüz B, Eid M. When risk communication backfires: randomized controlled trial on self-affirmation and reactance to personalized risk feedback in high-risk individuals. Health Psychol 2013;32(5):561-570. [PMID: 23646839]

Sheeran P, Harris PR, Epton T. Does heightening risk appraisals change people’s intentions and behavior? A meta-analysis of experimental studies. Psychol Bull 2014;140(2):511-543. [PMID: 23731175]

Weinstein ND, Klein WM. Resistance of personal risk perceptions to debiasing interventions. Health Psychol 1995;14(2):132-140. [PMID: 7789348]

Wimberly YH, Hogben M, Moore-Ruffin J, et al. Sexual history-taking among primary care physicians. J Natl Med Assoc 2006;98(12):1924-1929. [PMID: 17225835]

Resources for Consumers

June 2022

Patient Education Materials

AIDS Institute Clinical Guidelines Program:

- I Might Have Been Exposed . . . What Should I Do?

- Podría Haber Estado Eexpuesto al VIH… ¿Qué Debo Hacer?

New York State Department of Health:

- Beyond Status

- Emergency Contraception: What You Need to Know

- HIV/AIDS Basics & Other Resources

- HIV/AIDS and STD Testing

- Payment Options for Adults and Adolescents for Post Exposure Prophylaxis Following Sexual Assault

- Payment Options for Post‐Exposure Prophylaxis Following Non‐Occupational Exposures Including Sexual Assault

- Post-Exposure Prophylaxis (PEP)

- PrEP and PEP Information & Resources

- Rape Crisis Programs by County

- Sexual Violence Prevention Program

- STD Clinics in New York State

- What is PEP? Fact Sheet

New York State:

- Coalition Against Sexual Assault

- Office for the Prevention of Domestic Violence

- Office of Victim Services

- Safety and Health

- Sexual Assault Victim Bill of Rights

- Workers’ Compensation Board: Information for Health Care Providers

New York City: Where to Get PrEP and PEP in New York City

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention:

- HIV Risk Reduction Tool

- Post-Exposure Prophylaxis

- Preventing Needlestick Injuries in Health Care Settings

HIV.gov: Post-Exposure Prophylaxis

Migrant Clinicians Network: Sexual Assault

NAM Aidsmap: Post-Exposure Prophylaxis (PEP)

New York-Presbyterian/Columbia University Medical Center: Domestic and Other Violence Emergencies (DOVE)

U.S. Department of Labor Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA):